No, it’s not about Marilyn Monroe and John Kennedy – This is about Plants and George Washington

If you’ve ever been to Mount Vernon you know that George Washington (1732-1799) was a great gardener. Like most Virginia planters he started out as a tobacco farmer, but quit and turned to farming mixed crops. He rented Mount Vernon, with its modest house on a plateau overlooking the Potomac, from his brother, and then inherited it in 1761. Over time he came to own five farms of 7200 acres. Mount Vernon, some 500 acres, was his “Home Farm.” What’s most astounding is that he nearly tripled the size of the house and turned the plantation into a graceful and stunning landscaped park while fighting in the French and Indian War (1753-1758), serving in the Virginia House of Burgesses in Williamsburg (1758, 1765-1775), then commanding all Continental Forces in the Revolution (1775-1783), presiding over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia (1787), and serving as the first President of the United States with its capital in New York and then Philadelphia (1789-1797). He died only two years later. But he used that time away, even though responsible for the lives of thousands of men and the life of this untried nation, to think about his Home Farm.

His landscaping inspirations, ideas and influences came from other estates and the only landscape design book that he owned, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting of Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, etc. after a more Grand and Rural Manner than has been done before. Batty Langley, London (1722) https://archive.org/details/mobot31753000819141

His landscaping inspirations, ideas and influences came from other estates and the only landscape design book that he owned, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting of Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, etc. after a more Grand and Rural Manner than has been done before. Batty Langley, London (1722) https://archive.org/details/mobot31753000819141

Langley recommended that parterres “. . .should be uniform; because the Eye being struck with all their Parts at the same Time, each opposite side should be equal . . .” Further “. . . when we come to copy, or imitate Nature, we should trace her Steps . . . therefore when we plant Groves of Forest or other Trees, . . . no three Trees together range in a straight Line . . .” meaning they should be irregularly placed. He advised that “Parterres are most beautiful when entirely plain . . .with Grass,” suggesting an “octangular” open lawn planted on the sides with groves of trees and flowering shrubs interlined with serpentine walks. In addition to reading Langley’s book Washington visited and stayed at grand houses from time to time. While President in Philadelphia he befriended William Hamilton (no relation to Alexander) and visited his 600 acre “Woodlands” designed along the English landscape gardening design of irregularly placed groves of trees and shrubs with winding paths overlooking the Schuylkill River.

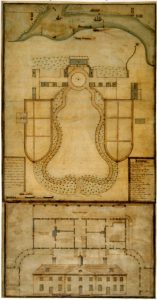

Washington designed Mount Vernon’s entrance along these lines – a nearly mile long bowling green of unobstructed view to the house, framed with a symmetrical serpentine drive on either side arriving at a circular lawn just in front of the house. Groves of trees and shrubs shaded the serpentine drive. On the outside of the tree-lined drive Washington designed and built symmetrical gardens, rectangular but rounded on one end, shaped like a medieval shield. Each of these gardens was about two acres in size and surrounded by a brick wall. One, called the Upper Garden he originally planted with a mixture of herbs, vegetables, fruits and flowers but gardens evolve and it became primarily a flower garden. Washington replaced the brick wall along one side with a conservatory. The other, The Lower Garden, was rectangles of fruit, vegetables, and herbs, enough to supply the household, numerous guests and the 90 house slaves. Additionally Washington grew starter plants and experimental plantings in a small “Botanical Garden.” A four acre garden called a vineyard did not succeed as a vineyard so it became a vegetable garden. A 1787 plan drawn by Samuel Vaughn shows the outlines.

(This is not a landscape design it was drawn after this was constructed.)

(This is not a landscape design it was drawn after this was constructed.)

How did Washington accomplish all this with his many, long absences? He had 90 house slaves and more than 200 who worked the farms and could be called upon if needed. He frequently wrote to Lund Washington, the plantation manager, with instructions. He hired head gardeners from Europe who were indentured servants. When he was home Washington did much of the work himself. He sowed seeds and marked them for identification. He grafted trees. He rooted cuttings. He planted and transplanted. He dug trees from the woods. He ordered trees by the wagon load. People sent him plants. One thing is clear from reading his letters and reading about him – he was never ever idle.

What did he grow? Trees and shrubs live a long time. As a result many have been identified. Flowers, vegetables, and herbs do not live as long so the species or varieties cannot be identified. A few of his trees are below. The flowers listed below are based on Washington’s letters, notes, or diary.

Trees and shrubs:

Trees and shrubs:

Aronia arbutifolia Red chokeberry

Calycanthus floridus Carolina allspice

Cercis canadensis Redbud

Cornus florida Flowering dogwood

Hibiscus syriacus Rose of Sharon

Hydrangea arborescens Wild hydrangea

Hydrangea quercifolia Oak leaf hydrangea

Ilex verticillata Winterberry

Kalmia latifolia Mountain laurel

Kerria japonica ‘Pleniflora’ Japanese kerria

Liriodendron tulipfera Tulip tree

Myrica pennsylvania Northern bayberry

Syringa vulgaris Lilac

Flowers

Flowers

Delphinium ajacis Larkspur

Digitalis purpurea Foxglove

Lobelia cardinalis Cardinal flower

Phlox divaricata Sweet William

Phlox paniculata Garden phlox

Yucca filamentosa Yucca

Additional resources: Washington’s Gardens at Mount Vernon Mac Griswold Boston, New York 1999; www.mountvernon.org/the-estate-gardens/